I went to the Isle Of Man to watch some motorcycle races.

These were not the (in)famous ‘Tourist Trophy’ (TT) races; those were held earlier this year, as they’ve been ‘most every year since 1907. The IOM TT races are contested by the best young & fearless talent, on the latest & fastest two-wheeled machinery. The IOM TT is billed variously as ‘The World’s Ultimate Road Race’ (by the promoters) and as ‘one of the most dangerous racing events in the world’ (by knowledgable observers). A few moments spent on youTube can demonstrate the IOM TT’s essential character: ludicrous speed on narrow roads lined with trees and stone walls. Full-course average speeds are around 135mph.

I went to the Isle Of Man to watch some motorcycle races.

These were not the (in)famous ‘Tourist Trophy’ (TT) races; those were held earlier this year, as they’ve been ‘most every year since 1907. The IOM TT races are contested by the best young & fearless talent, on the latest & fastest two-wheeled machinery. The IOM TT is billed variously as ‘The World’s Ultimate Road Race’ (by the promoters) and as ‘one of the most dangerous racing events in the world’ (by knowledgable observers). A few moments spent on youTube can demonstrate the IOM TT’s essential character: ludicrous speed on narrow roads lined with trees and stone walls. Full-course average speeds are around 135mph.

The TT is iconic, but for me as a spectator, kind of one-dimensional. The motorcycles all look and sound and perform alike. You’ve got to check the number as it goes by to know one from another. I don’t have a favorite rider to cheer for, and I lack the long term association with the race that would make me keen to follow the tiny differences.

The other races held on the island, the ones I attended, were the Manx Grand Prix and the Classic TT. The first of these is essentially a qualifier for riders hoping to graduate to the TT; bikes are somewhat smaller and somewhat slower, and the competition is a bit — just a bit — looser. That makes for a funner pit – riders and mechanics may occasionally smile and joke, which I doubt you see at the TT. And the second of the races is a distinct animal altogether.

The ‘Classic TT’ is populated with older bikes. The motorcycles were manufactured as old as the 1950s and as new as the 1980s. There’s a tremendous variety of sounds, sights, styles — a veritable cornucopia of mechanical expression. The set as a whole describes the evolution of racing motorcycles, with the path of improvement laid out in physical examples rather than pictures or text. And not ‘as seen in museums’, though many examples are collection-quality; these are here to race.

They’re sometimes piloted by modern stars, but more often by vintage riders who won various TT classes back in the day. From my experience, neither the older technology nor the sometimes older riders lead to a lessening of commitment. The fastest of the Classic TT are circling the course at around 120mph average.

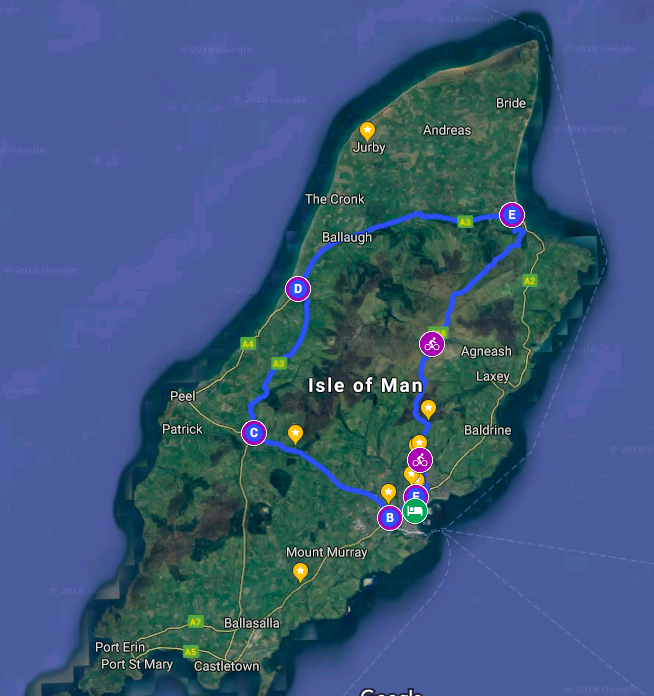

The ‘TT course’ is a linking of four main roads on the island. The A2, southbound through downtown Douglas; west on the A1 to Ballacraine Corner; the A3 to Kirkmichael and north to Ramsey; and then the A18 up across Snaefell Mountain back to Douglas. It’s 37.75 miles in length. During practice, or the races, officials close all of it to other traffic. Practices are 2-to-3 laps; races are 2-to-4 laps. That makes the Classic TT Final about eighty minutes long. It’s hard for me to imagine the level of focus and concentration that’d take.

I went to IOM with two long-time motorcycling partners: Scary Don Siewert, and my younger brother Anton.  I’ve ridden with both of these guys for decades. They’re not stodgy, but they’re not psycho. Well, Don used to be psycho, but he’s mellowed. I trust ’em. On Friday, Saturday, and Monday mornings, before breakfast, the three of us made a lap of the TT course. Each time we climbed the summit of the mountain portion, treacherous gusty winds pushed us around on the road. There were painted stripes (slippery!) and iron drain grates (disturbing!) throughout. The off-camber shaded twisties near Glen Helen always seemed moist. So many blind corners… we all knew IOM’s reputation, and these circuits did nothing but cement that reputation in our minds. We were running at, or somewhat above, the speed limit, as the roads weren’t closed, and it took us 58 minutes to make the round. The Classic TT racers were doing it in ~22 minutes.

I’ve ridden with both of these guys for decades. They’re not stodgy, but they’re not psycho. Well, Don used to be psycho, but he’s mellowed. I trust ’em. On Friday, Saturday, and Monday mornings, before breakfast, the three of us made a lap of the TT course. Each time we climbed the summit of the mountain portion, treacherous gusty winds pushed us around on the road. There were painted stripes (slippery!) and iron drain grates (disturbing!) throughout. The off-camber shaded twisties near Glen Helen always seemed moist. So many blind corners… we all knew IOM’s reputation, and these circuits did nothing but cement that reputation in our minds. We were running at, or somewhat above, the speed limit, as the roads weren’t closed, and it took us 58 minutes to make the round. The Classic TT racers were doing it in ~22 minutes.

The course was fascinating, the whole island scenic, and the practices and races entertaining; but the high points for us came from the stupefying range of motorcycles there. Some that none of us had ever seen, and some in great profusion in the amusing presence of so.many.clubs dedicated to such-and-such odd model. There were twelve riders from Sweden who’d come over on their BSA A65s (none newer than 1966). There were the similarly Scandinavian fans of Kawasaki W650s and W800s, motorcycles rare in the U.S.A. but quite a cult classic elsewhere, judging from the hordes of ’em swarming the paddock – each bike customized to suit the owner’s individual preferences. The Ducatis travelled in packs, we saw clutches of older grey-haired couples running about on tiny minibikes like cheerful Hells Angels, the Triumph Bonnevilles were strewn about four to each corner. PLUS the Benellis and Guzzis and holy shit a Harris-framed GS1000, there’s a knot of Greeves, every kind of motor wedged into Norton frames, with tank badges hinting at the type of hybrid: Harton for a sportster engine; VInton for a BlackShadow mill; a big Yamaha V-Twin with the engine case ident polished off in another.

There were sidecars  and race bikes and a chopper, I think. There were roving bands of dual-sport riders ‘scrambling’; there were all the latest fastest hyperbikes with their intense owners. There were older two-strokes so heavily customized and updated that only the core of the original remained.

and race bikes and a chopper, I think. There were roving bands of dual-sport riders ‘scrambling’; there were all the latest fastest hyperbikes with their intense owners. There were older two-strokes so heavily customized and updated that only the core of the original remained.  And this whole soup of two-wheelers was in constant motion about the island, heading to the museums, working up the back roads to reach a viewing spot on the course, filling the restaurants and inns, every parking lot an impromptu motorcycle show, most every conversation one about the elegant mode of motion which depends on balance and grace, and the crafted mechanisms that enable it.

And this whole soup of two-wheelers was in constant motion about the island, heading to the museums, working up the back roads to reach a viewing spot on the course, filling the restaurants and inns, every parking lot an impromptu motorcycle show, most every conversation one about the elegant mode of motion which depends on balance and grace, and the crafted mechanisms that enable it.

There are precious few ‘appliance’ motorcycles. The notion of vehicles-of-anonymous-utility does not mesh well with the gentle art of cycling; what would be the point? Motorcycles move you in both the physical world and in the inner sanctum. We were moved. And then we came home.

I must say that, sadly, not all of the racers did come home. Even at the Manx GP and Classic TT, the stakes are high, and the penalty for failure is severe.