Tarmac rallies can be hard on tires. Strike that; tarmac rallies are hard on tires. The Newfoundland roads take it a step further than that-the Rock’s stages have hazards for wheels as well.

The best approach is to avoid all the hazards, of course. But just in case you don’t, be sure to bring the two spare tires allowed by the organizers. Ideally those tires would already be mounted on wheels, ready to bolt onto the car.

When we Targa’d in 2015, the station wagon easily held both our spares; in 2016, the coupe could carry only one spare inside, strapped down behind the front seats. But this year, in the Cayman, there’s just no room in the cabin for a spare… you’d have to run without a co-driver and use the passenger seat for tire haulage. And that won’t work on a stage.

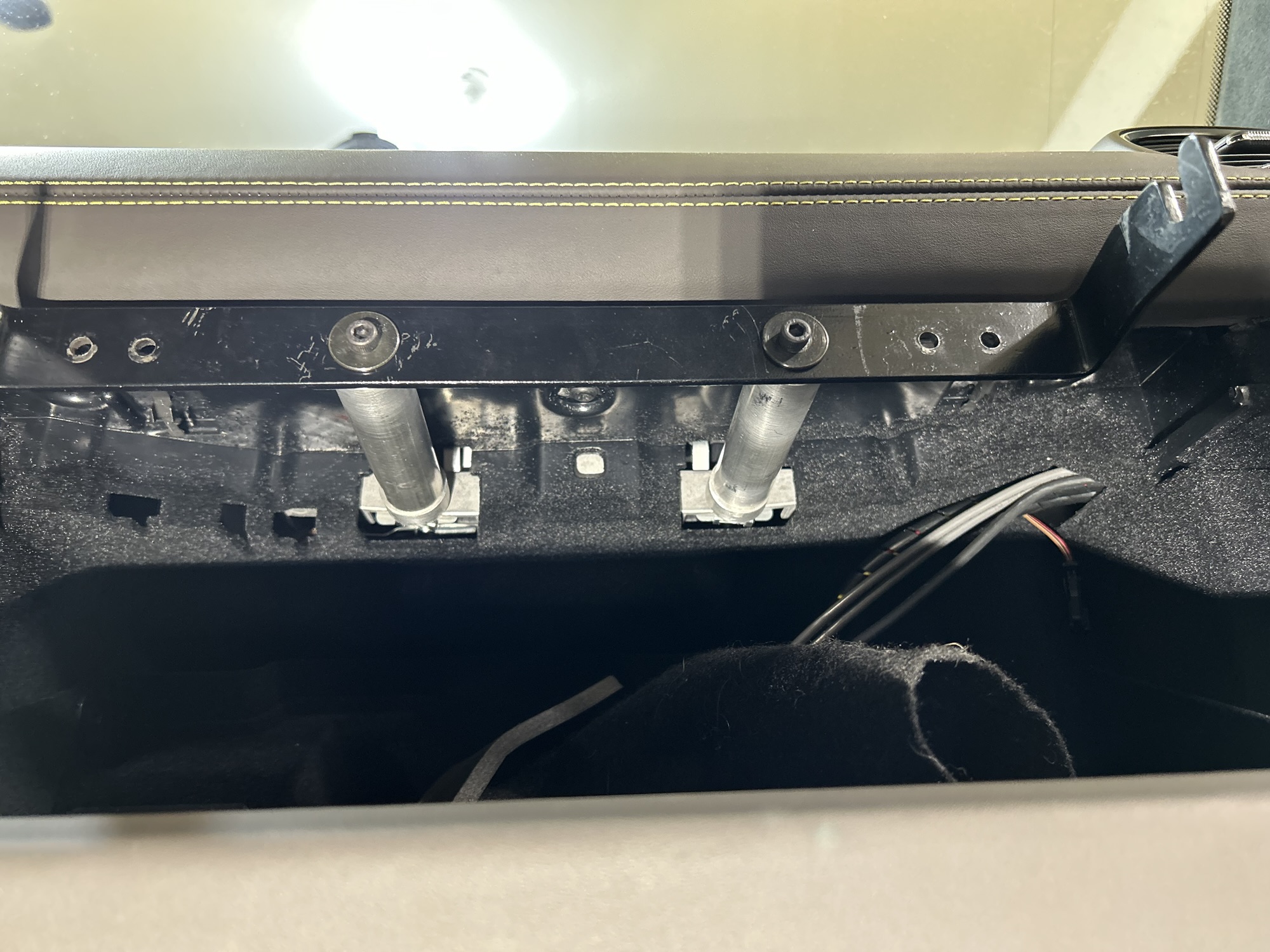

How about putting a mounted spare in the frunk?

How ’bout not, says this picture.

But you simply must carry at least one ready-to-go spare. Targa runs all day, and you are never close to a commercial area. If you’re blessed with a service crew (we are not), you may not be close to them.

You simply must carry one with you.

Well then, if we must…

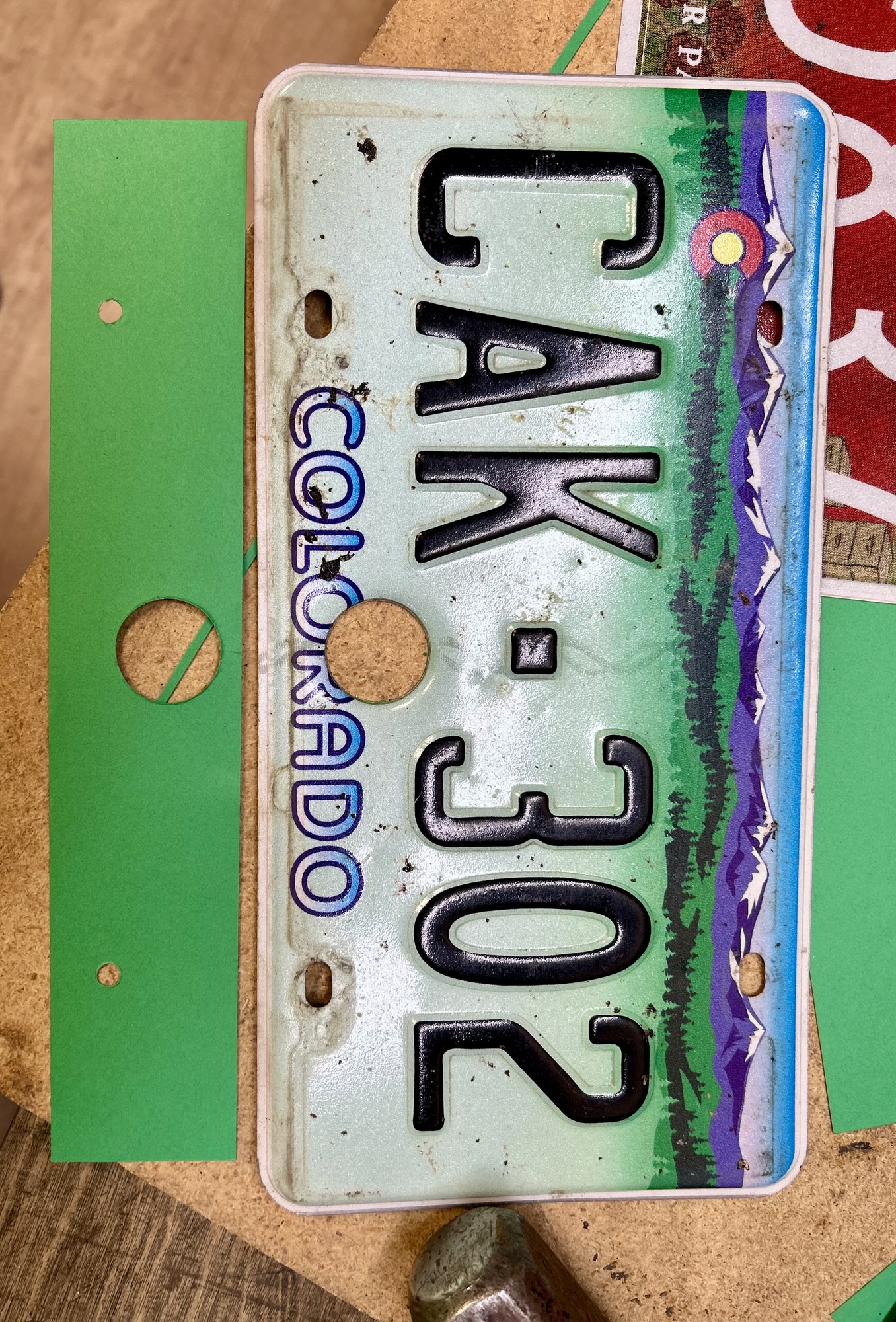

Now the hood closes at least. That’s a used 991 hood, by the way; same part number.

Call it a “rain shield”.

Slightly less offensive in Racing Yellow. But it still needs something.

Ah, that’s better. That’s a proper rally car look.

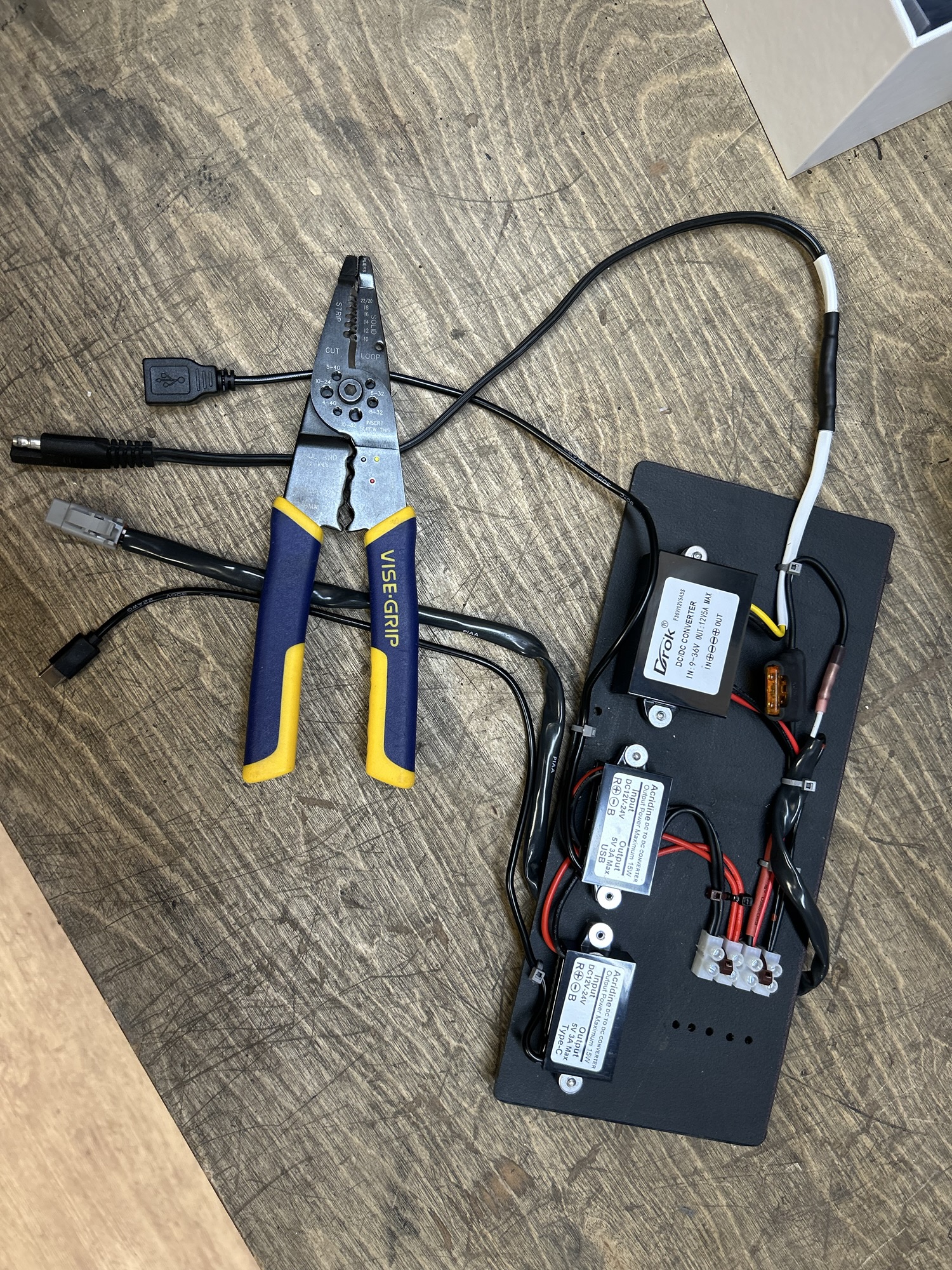

Under the bulge, the spare is secured with a couple tether points in the frunk walls and a long surcingle of nylon strapping. The jack and torque wrench (118 lbs-ft!) are nearby.