All moments of life are colored by our emotions. None of us, in sensing – in seeing – is a neutral slate upon which experience is writ. We bring to every event a pre-setting, a state of ourselves; and what we feel in the offing is the combination of that state and the actual sensations of the event. This is what makes the anticipated kiss sweeter, the apprehended danger the more frightening, and the overdue respite more satisfying.

The Flying Pickle, Bonneville Speed Week 2018

Since Pickle first started trying to run 200 miles an hour, five years have passed. Most recently, in 2017, with a fresh motor and a ‘hot’ tune, we spent a day and a half driving to the Bonneville Salt Flats, only to find that the car’s ECU settings weren’t suited for the conditions, and the car made no more than 142 miles per hour. Our drive home was full of self-recrimination and regret.

This year we had a detailed plan. The tuning issue had been addressed with a session on the chassis dynometer. For everything else, we organized a series of work days, one a month, from March through July. We added sensors, produced logistical aids like towbars and a detachable muffler, and tried to validate that the car’s mechanical components were ready for 200 miles an hour. But it’s almost impossible to ‘test’ a land speed car… one needs many miles of road, with wide-open throttle, to reveal the real issues.

By the final work day, we were running short on things to do. We began talking about “What extra body parts should we bring to run in a second competition class after we break the record we’re targeting?” Oh, we were confident.

Since we were ahead of schedule, we left one day early, to reach the salt on Sunday, the second day of SpeedWeek. We wouldn’t be able to run Sunday, but we expected to do so on Monday. My imagination had us qualifying for the 200 mph record Monday afternoon, making the record run early the following morning, and thus being able to attend the RedHat (200mph Club) banquet scheduled for Wednesday night. I brought a suitcase full of dress shirts, because I thought we’d have time to kill between what promised to be one fantastic run after another.

Monday

No problems on the 11 hour drive from Battleground yesterday. We set up our pit and went over to register. Quite a few folks down there know the Pickle, and the registrar arranged to give us a cheaper pre-paid entry from a team that didn’t make it. A crew of safety inspectors checked the car over, and gave it thumbs up. We headed to the starting line.

Unlike 2017, when we queued at least four hours for each run, this time we waited perhaps half an hour. We barely had time to warm the motor up. We pushed Pickle off the line, and at around 50 miles an hour the car pulled away… not running completely cleanly, but obviously better than 2017. But as the push truck raced down course on the Return Road, the radio told us that the Pickle was already pulled over, barely past Mile Two.

We reached the car quickly. The driver told us there’d been a terrible noise from under the hood, and then the motor revved freely, with no drive to the wheels. He thought the car had thrown its chain. This felt distressingly familiar.

The chain drive system on the car is its Achilles’ heel; but what do you expect when you’re putting three times the normal power through it? One task on an early work day was ‘check the the chain drive system’, but at that time, all looked well. We saw no need for disturbing it, and besides, we didn’t see any obvious design improvements to make. The chain drive was one of the few systems that we didn’t fortify before we went to Bonneville; now that neglect came home to roost.

In the pits, we raised and supported the car, and removed the belly pan. Bits of broken chain were lying on the topside of the pan. Worse than that, we could see that the main sprocket, the one attached to the axle, was badly damaged. We set about removing the axle and sprocket for closer inspection. It is a tricky and annoying job, even in a shop, where you have a full toolbox and the car overhead on the lift. Now we were forced to do it lying flat on our backs, with limited maneuverability for tools and limited space for mechanics.

By 4 o’clock, we had the axle out. Then we saw the full extent of the damage.

We think the axle moved forward on one side in response to the pull of the motor. The chain then walked up the side of the sprocket, and as there’s very little slack in the system, the chain got real tight. The master link sheared off both pins in the end plate before failing completely. Then it was mostly a metal blender down there. Several teeth on the main sprocket were missing, or fractured. The chain was torn to pieces. The steel chain guard was mangled. Luckily, the engine sprocket was only lightly marred, and miraculously the engine cases showed no damage at all. (dang, that’s lucky. -ed)

There was no chance of continuing with that sprocket. And – we brought no spare, as working on the axle system was deemed ‘too difficult’ for the salt: why provision for actions that you cannot imagine taking? But now we had no choice but to work on it. If we couldn’t repair the chain drive system –and find a way to ensure that the axle would stay put under maximum power – we might as well go home; and nobody wanted to make another drive like 2017’s.

On the side of the sprocket was a manufacturer’s mark; not a part number, just a brand. An Internet search revealed that their factory was in Utah, somewhat south of Salt Lake City. (dang, that’s lucky. -ed) We found their phone number and called. Explaining our situation, we asked if they had a record of the sprocket, but they did not. The owner suggested that we measure our sprocket, pass those measurements to him, and they would do whatever it took to build a sprocket, and get it to us by mail by Wednesday.

But we were suddenly very conscious of time. Kicked off the salt at 8 PM, we returned to our casino/hotel and worked on a more expedient plan.

Tuesday

We dispatched two members of our team, at 4 AM, to drive to Richfield, Utah, and be at the sprocket-makers‘ shop when they opened. The rest of us headed out to start repairs and work on a more secure mounting system for the axle to resist the 400 hp of the motor.

By Tuesday midday the remote team had returned with a replacement sprocket. The rest of the day, we worked painstakingly to install the axle shaft, chain, and our one spare crush-fit master link for the chain. Conditions were ‘normal’ on the Salt in August, which is to say abnormal for most every other place on Earth. Blinding sun, a dearth of humidity, an occasional breeze bringing only parched air.

Under the car, we rotated shifts of workers. It went on all day. We left the salt Tuesday evening, not yet ready to run.

Wednesday

At daybreak, we headed back out. We’d try to implement our best idea for positively locating the axle. Part of this involved mechanical interference, part of it involved travel–limiting shims, and part of it involved assembling the main supporting members with prodigious torque on their fasteners. Space is very limited in the drivetrain area, and none of our tools was a perfect choice for leverage. We put two mechanics on the wrench simultaneously, one fore and one aft. Fingertips straining, proceeding in phases, we tightened the fasteners to the limit of our paired power.

While Pickle was still on jackstands, we test-ran the motor, then re-checked the drivetrain. The chain had loosened very slightly, so we took pains to readjust it. Then the belly pan went on, and we towed back to the start line.

Again our wait was short, and we pushed off within 30 minutes. This time she made a longer run, pulling well ahead and out of sight.

Over the radio, the timer read off the speed: 195mph in Mile Three! That’s 20mph faster than Pickle’s ever done before! The fourth mile was slower, though, and the driver pulled off before Five. This suggested another failure.

There were two failures. Our driver said the motor’d ‘gone soft’ around the Mile Four mark, and then shortly after, the car developed a strong pull to the right. He cut the run early. We towed back to the pits, and Pickle went back up on jackstands. Before long the cause of the pulling was obvious: the outer CV joint on the left halfshaft was completely destroyed. Blackened, scarred parts were falling out of the CV cup. With that CV joint in pieces, the power axle had no connection to the left front wheel; and without both wheels taking the power, the car was undriveable.

One positive note was that the sprocket system was intact, and looked to be operating as intended.

But again the day was winding down, and again the parts situation was dire. Sprockets are, in some sense, simple. A generalized factory can produce a wide range of them. Simplicity was what let our sprocket supplier make replacements while we waited. But the destroyed outer CV joint was a part built in 1964, in Sweden, from drawings and by machines long since retired. The relative obscurity of the SAAB 96 meant, also, that normal auto parts suppliers would not stock remanufactured units. We scoured the Internet again, and found one possible shop in Utah that might –might– have the vintage bit, but they weren’t answering the phone. It was getting late. The ‘lazy days of SpeedWeek’ had yet to materialize.

Without a CV joint, we were dead in the water.

Then someone hit on the solution: in Portland is a shop that (I daresay) specializes in SAAB 96s, and we had the owner’s personal cell phone number. While driving off the salt, we called him, and he was immediately on board. Yes, he had spare CV joints ready-to-go; yes, he had a special tool needed to install them; yes, he could create a video demonstrating the use of the tool for the tricky bits; and yes, he would dispatch his assistant to FedEx to overnight the parts and tool to us. The assistant called from the shipper, and we selected the best combination of delivery time and distance for us to drive. (dang, that’s lucky. -ed)

It was the best plan we had, and could perhaps work; but I deny 100% that any of us were ‘hopeful’ at that point.

And what about the motor softness? Had we started to cook some internal engine part, like an exhaust valve, or perhaps the turbocharger itself? That night in the hotel, we reviewed all our data, and tentatively diagnosed the problem as a displaced boost sensor hose (best case) or a failed sensor, or a split manifold, if we were less lucky.

Thursday

It felt like a repeat of Tuesday… two members drove toward the rising sun, east to Salt Lake City, aiming to reach FedEx at 9am and retrieve the package. The rest of the team hit the salt early to disassemble the broken joint from the wheel, and get ready to install the replacement. By noon, the parts were in the pits, and assembly commenced.

The fragility of the drive system under the increased power load demanded meticulous technique; things would barely hold together if everything was done perfectly – if anything wasn’t, it’s scrap time. But SpeedWeek was leaking away; Thursday’s qualifying runs must be backed up Friday morning; and any qualifying runs on Friday have to happen before 11am. Our cushion, our window for qualifying, was shrinking. So we had to rush, but we could not rush.

There was a grim intensity in the work area.

A displaced boost sensor hose was found, and fixed. (dang, that’s lucky. -ed) The CV joint was on. No time now to test the system, we settled for listening for bad noises while towing the car to the starting line. There were none, just a smooth whirrr on the way. Again we waited but a short time for our run. The driver babied the car off the start, and the pushbar was hard against Pickle ’til 80mph. Then Pickle was away, accelerating strongly, and before we lost sight of her, a clear salt roostertail could be seen – the sign of good speed.

She went 205mph through Mile Five, 3mph better than the existing record.

We’d qualified for a run on the record the next morning; ’til then, we’d be confined to Impound. We towed in, finally, first time of the week, and spent a few hours charging batteries, refilling fluids, and adjusting the chain. When our allowed work-time was up, we drove off the salt in a mix of excitement and terror. This had been the first run of the week without a serious drivetrain failure. Would our ‘improved’ axle mounts hold up for another 200+ mph pass tomorrow?

Doubt is like the sea; it’s always there, and when it rises it may overwhelm thee.

Friday

We were at the edge of the salt in full darkness, part of a line of competitors who were likewise facing Record Runs. Around 6am the officials led us all out to Impound, and we warmed her engine, then hooked up to tow Pickle to the start.

We wanted to just face whatever would happen, and other folks were delaying, so we jumped ahead in line at their urging, and we were next.

Our fourth run of the week. The starting line checklist is more familiar now, check and double-check the harness and hood locks, get 100lbs of ice into the intercooler, pull the safety pins out of the parachute and halon fire extinguishers, and … ready to push.

Pickle’s motor, running raspy below 8500rpm, cracks and snaps as the big Chevy push truck leans into the work. By 45mph Pickle’s ready, spinning both fronts as it pulls away from us. We dive off the track for the Return Road, chasing her on a parallel track toward Mile Five, and Pickle’s flying, roostertail up, receding from our vision, out of sight in moments.

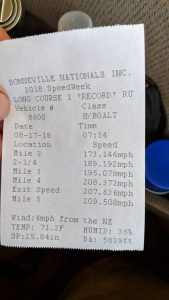

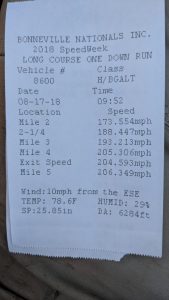

The timer reads the splits of the measured miles:

Mile Two 173 … Mile Three 195 … Mile Four 208 …Mile Five 209 mph

cheering in the push truck

Throw the chute in the trunk, pin the fire bottles, let’s go to Technical Inspection and get this thing certified.

Knowing that one element required is an engine measurement, we swing by our pits to get a spark plug socket to enable that measurement. We approach Tech Inspection, then, from the pit side, not from the Return Road. Triumphantly, we pull up to the station; and then in two sentences our joy is shattered. We’ve violated a basic rule by leaving the Return Road. Our detour to the pits is disqualifying. An appeal is made, other evidence of our innocence offered, but to no avail: our record attempt is null and void.

The air seemed hollow. Our energy drained away, and self-consoling rationales began forming in our minds. I doubt any of the team believed that we had the necessary time to re-qualify by 11am, nor believed that the patched-up drivetrain could handle two more passes at record-breaking speed.

But bystanders — plus the Tech Inspectors themselves — thought otherwise. They encouraged us. One spoke of another team, normally requiring four hours of maintenance between runs, who this morning had no choice but to attempt a two-hour turnaround. We had never prepared our car in less than three hours … it seemed hopeless.

We feel wrung out, like a toothpaste tube that’s empty.

Or is there one more ribbon in there? Perhaps we should try.

In the pits, we renewed fluids and fuel, partly charged the batteries, ignored the chain, packed the chute, and made it to the starting line. We’d have to run at least 203mph to be granted a record attempt. The motor was still warm, which shortened our preparation. The starting official was gracious and positive. We ran the checklist by the book, pins and belts and PUSH OFF!

Still raspy, Pickle rode the Chevy’s pushbar ’til 50mph, then surged away. The announcer didn’t understand why we were so quickly running again, and dithered on the radio… Meanwhile, Pickle’s got a roostertail, go baby go go go.

Through Mile Five, pulling strong, 206mph … a qualifying speed.

Now down at the end of the course, driver’s already stowed the ‘chute in the trunk, we have little time to waste. Driver says the car ran straight and strong and true. Up the Return Road and into the Impound Area, directly, with no deviations. Now we must again turn this car, get it ready for another pass in a couple hours.

The generator roars, powering the battery charger. We jack her up and pull the belly pan. Chain’s just slightly loose, one 32nd of a turn on the adjustment bolt. Fill the tank with A8-D, a $30/gallon racing gasoline that smells like … I dunno, but it smells powerful. Our turbo boost line is still secure. The datalogs say all systems are go.

The sun is positively blazing, throwing sharp edged dark shadows. Any shade or shielding is a godsend. Re-pack the chute, leads and lines stretched out on the white crust of impound. Can we look at…? No, we are out of time, and must run as we are.

A handful of qualified cars line up for the tow to the start. The course will close in an hour, the end of Speed Week.

At the line, the remaining spectators gaggle up, pulling for our chances, smiling at the gamble. Perhaps they don’t know it’s a gamble, they don’t know what we know, now, about pillow block bearings and CV joints and the special swaging it takes for a 530XWV2 chain’s master link; they don’t know about 2017’s humiliating 142mph runs. They don’t know about 2013’s burned valve, 2014’s rain-out of the whole meet, the poor salt of 2015, the chagrin of our disqualification five hours ago. We feel these things, and they have us totally engaged.

Push truck’s behind and touching, electrical umbilical’s plugged in. Pickle starts and is warming up. Checklist says pull the fire bottle pins out, parachute pin out, pour in the intercooler ice, get the cameras running. Driver’s inch-thick fireproof suit is fastened, seven-point harness rigged, window net up; pull out the auxiliary muffler. rummm rummm rummm goes to RUMP RUMP RUMP. Ready to start.

The official gives us the course.

The Chevy push truck has a 496 cubic inch V8, and we pull off the line smoothly then I bury the throttle. Pickle’s riding the pushbar, pointed at the horizon … starting now to sound more alive, drone turning to a howl as she rips away from the truck and is on her own.

The crew is silent as we hurtle down the Return Road chasing Pickle. The announcer’s been clued in to our plight, though he avoids mention of our rule violation, and he’s keenly tracking the timing numbers. There’s a delay while he calculates the average velocity, then he delivers the result: 207.153 mph, a new land speed record in 1500cc Blown Fuel Altered.

In the push truck, we snap from silent to loudly giddy, amazed that we recovered from our disqualification, amazed that our field repairs held, amazed, really, that the serious breakages we had Monday and Wednesday were even repairable on the Salt. If we’d come down to Bonneville on our original schedule, we’d have run out of time. So many things that could have gone wrong … did not.

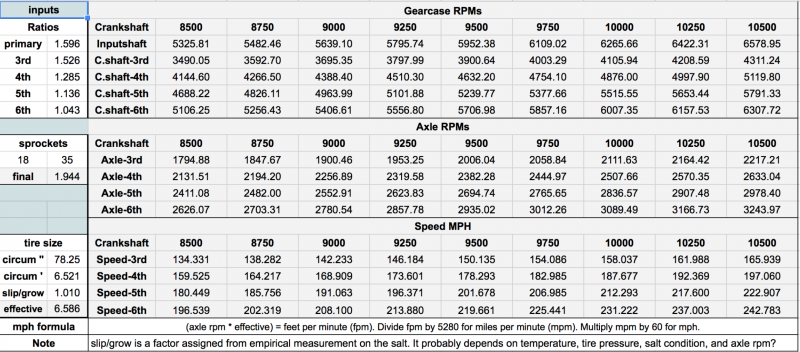

At the end of the course, there stands the driver. He has no speedometer, but he does have a big tachometer, and he knew if it made 9800rpm through a mile that’d be enough. He knows.

We towed … where? Directly to Tech Inspection. Directly.

The motor size was verified and the record, certified. We were the last car to make a run at Speed Week 2018.